On July 3, 1985, the world of mainstream science fiction was changed forever. Before Back to the Future hit, there had never been a truly massive time-travel blockbuster. Back in 1960, The Time Machine was a modest success with $2.61 million, but, broadly speaking, the sci-fi subgenre of time travel TV and film was relatively untested before Back to the Future was released.

So, calling Back to the Future a surprise hit in 1985 wouldn’t be wrong, and, in some ways, is a massive understatement. As has been extensively documented (particularly in Caseen Gaines’ excellent 2015 book We Don’t Need Roads), the production of the original Back to the Future was a troubled one, specifically because the entire movie was nearly shot before director Robert Zemeckis realized he wanted to trade Eric Stoltz for Michael J. Fox in the role of Marty McFly. How many other classic films completely reshot nearly everything with a different lead actor and lived to tell the tale?

And yet, 40 years after its release, the most remarkable thing about Back to the Future isn’t necessarily the process by which it was crafted by Zemeckis and screenwriter Bob Gale. Instead, the brilliance of Back to the Future is the result. It’s a classic film beloved by multiple generations. It also makes little to no sense, and some of the basic assertions of the film fall apart under the tiniest bit of scrutiny. After 1985, Back to the Future became the ultimate shorthand for all discussions about time travel, paradoxes, and alternate timelines. But that doesn’t change the fact that two aspects of the film are narratively chaotic, at least on paper.

First, the fact that Marty and Doc are friends to begin with is never explained nor fully addressed within the first film, or even the subsequent sequels. Why a high school kid is buddies with an eccentric neighbor who steals plutonium is perhaps less realistic than the sci-fi hijinks of the time travel itself. In theory, the fact that Marty meets Doc in 1955 via time travel neatly solves this mystery: The reason why Doc and Marty know each other in 1985 is because they always have; their friendship is a predestination paradox that powers the propulsive story engine of the movie better than any hard-to-obtain time machine fuel.

Except the movie doesn’t really say that at all, at least not outright. Assuming that Marty creates a second, slightly better timeline in which Doc wasn’t fatally shot by the terrorists and in which all members of his family are more conventionally successful and stable, this suggests that the original timeline — the one where Marty didn’t have his heavy duty black pickup truck and Doc didn’t read the letter — must be a timeline that either collapsed or is no longer inhabited by a versions of Doc, Jennifer, and the McFlys that we’re supposed to think about.

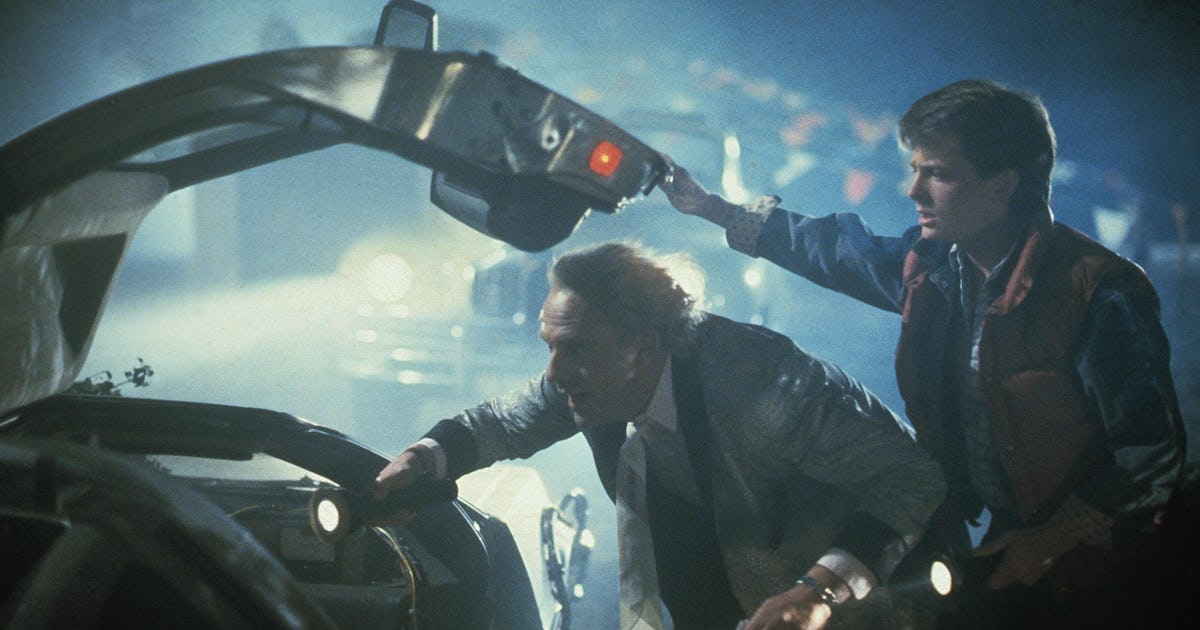

Christopher Lloyd, Michael J. Fox, and Lea Thompson in 1955 in Back to the Future.

Amblin Entertainment/Universal Pictures/Kobal/Shutterstock

So then, in the first timeline, how did Marty and Doc meet? Perhaps we’re meant to think that the first timeline only exists in a kind of temporary dimension, a sort of collapsing universe from which Marty comes, but isn’t destined to stay in. If that theory is true — which again, isn’t made clear by the movie itself — it would explain the second biggest oddity with the film.

Because the film hinges on the possibility that Marty may never be born if his parents don’t meet, the climax famously features a moment when he starts to fade away. Prior to this, parts of his family’s photographs start to fade, too, indicating that his timeline (the ideal one or the original one) is slowly being erased from existence. But why is this gradual? Does the timeline know that George and Lorraine might not kiss and fall in love? And more relevantly, does it know that they might? How? Who is keeping score in terms of the timeline? Why is the photograph fading, rather than disappearing?

The movie didn’t need for Marty do jam out on stage to work. And that’s why we love it.

Sunset Boulevard/Corbis Historical/Getty Images

None of these things are flaws. Instead, the scrutiny we now put on the movie comes from decades of mainstream time travel stories that followed. In Star Trek: The Next Generation or Doctor Who changes to the timeline often appear evident almost instantly, making Marty’s faded photograph and his dueling present tenses a kind of time travel anachronism. The rules of Back to the Future follow their own set of timey wimey logic, even if that logic only exists to serve the narrative.

In this way, Back to the Future is a triumph for the simple fact that time travel nerds still put up with it. The notion that omniscient time gods are watching all these events unfold seems to be the easiest explanation for why things happen the way they do. And of course, those creatures do exist. They’re us, the audience. Back to the Future works, despite some of its contradictory plot points, because it puts the ultimate perspective back on the viewer. It proves that science fiction stories can have plot holes or confusing cause-and-effect dominoes, as long as the story values one thing above all. Back to the Future wants the audience to like it. It wants to be a crowdpleaser, and it wants this status more than it wants to make sense.

And that reason, its warmth and charm, is the reason why we love it. As a science fiction story, it’s basically just okay. As a cinematic magic ride, full of friendship, family, and love, it’s still — despite two sequels — one of a kind.

Back to the Future is streaming on Hulu.

Source link

Movies,Science Fiction,movies,science-fiction,entertainment,movie-tv-anniversary,time-travel,inverse-recommends-movies,homepage,hp-latest,adex-light-bid

Average Rating